Which of the Following Statements Can Be Used to Prove That Carbon Is Tetrahedral?

Truth Tables, Tautologies, and Logical Equivalences

Mathematicians normally use a two-valued logic: Every argument is either True or Simulated. This is called the Law of the Excluded Middle.

A statement in sentential logic is built from elementary statements using the logical connectives ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . The truth or falsity of a statement built with these connective depends on the truth or falsity of its components.

. The truth or falsity of a statement built with these connective depends on the truth or falsity of its components.

For example, the chemical compound statement ![]() is built using the logical connectives

is built using the logical connectives ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() . The truth or falsity of

. The truth or falsity of ![]() depends on the truth or falsity of P, Q, and R.

depends on the truth or falsity of P, Q, and R.

A truth table shows how the truth or falsity of a chemical compound argument depends on the truth or falsity of the elementary statements from which it's constructed. And then we'll start by looking at truth tables for the v logical connectives.

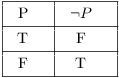

Here'southward the tabular array for negation:

This tabular array is like shooting fish in a barrel to sympathize. If P is true, its negation ![]() is false. If P is simulated, then

is false. If P is simulated, then ![]() is true.

is true.

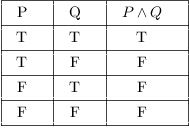

![]() should exist true when both P and Q are true, and false otherwise:

should exist true when both P and Q are true, and false otherwise:

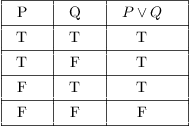

![]() is truthful if either P is true or Q is truthful (or both --- call back that we're using "or" in the inclusive sense). It'due south simply false if both P and Q are faux.

is truthful if either P is true or Q is truthful (or both --- call back that we're using "or" in the inclusive sense). It'due south simply false if both P and Q are faux.

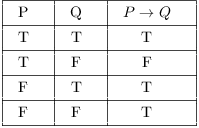

Here's the table for logical implication:

To understand why this table is the fashion information technology is, consider the following example:

"If y'all get an A, then I'll requite you a dollar."

The statement volition be true if I keep my promise and false if I don't.

Suppose it'south true that you go an A and information technology's true that I give you lot a dollar. Since I kept my promise, the implication is truthful. This corresponds to the first line in the table.

Suppose it's true that you get an A but it's false that I give you lot a dollar. Since I didn't keep my promise, the implication is false. This corresponds to the second line in the table.

What if it's false that yous become an A? Whether or not I give you lot a dollar, I oasis't broken my promise. Thus, the implication can't be false, so (since this is a two-valued logic) information technology must be true. This explains the last two lines of the table.

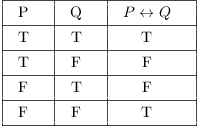

![]() means that P and Q are equivalent. And then the double implication is true if P and Q are both truthful or if P and Q are both false; otherwise, the double implication is false.

means that P and Q are equivalent. And then the double implication is true if P and Q are both truthful or if P and Q are both false; otherwise, the double implication is false.

You should call back --- or exist able to construct --- the truth tables for the logical connectives. You lot'll use these tables to construct tables for more complicated sentences. It's easier to demonstrate what to do than to depict it in words, so you'll see the procedure worked out in the examples.

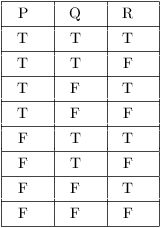

Remark. (a) When you're constructing a truth table, y'all have to consider all possible assignments of Truthful (T) and False (F) to the component statements. For case, suppose the component statements are P, Q, and R. Each of these statements can exist either true or false, so there are ![]() possibilities.

possibilities.

When you're listing the possibilities, you lot should assign truth values to the component statements in a systematic fashion to avoid duplication or omission. The easiest approach is to use lexicographic ordering. Thus, for a chemical compound statement with three components P, Q, and R, I would list the possibilities this way:

(b) There are different ways of setting up truth tables. Yous tin can, for case, write the truth values "under" the logical connectives of the chemical compound statement, gradually building upwards to the column for the "primary" connective.

I'll write things out the long manner, by constructing columns for each "slice" of the compound argument and gradually edifice up to the compound statement. Whatsoever style is fine as long as you show enough work to justify your results.

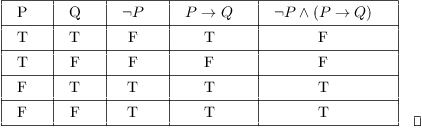

Case. Construct a truth table for the formula ![]() .

.

Beginning, I list all the alternatives for P and Q.

Next, in the third cavalcade, I listing the values of ![]() based on the values of P. I use the truth table for negation: When P is true

based on the values of P. I use the truth table for negation: When P is true ![]() is simulated, and when P is false,

is simulated, and when P is false, ![]() is true.

is true.

In the fourth column, I list the values for ![]() . Bank check for yourself that it is only imitation ("F") if P is true ("T") and Q is false ("F").

. Bank check for yourself that it is only imitation ("F") if P is true ("T") and Q is false ("F").

The fifth column gives the values for my compound expression ![]() . It is an "and" of

. It is an "and" of ![]() (the third column) and

(the third column) and ![]() (the 4th column). An "and" is true but if both parts of the "and" are true; otherwise, it is false. So I look at the tertiary and fourth columns; if both are true ("T"), I put T in the fifth column, otherwise I put F.

(the 4th column). An "and" is true but if both parts of the "and" are true; otherwise, it is false. So I look at the tertiary and fourth columns; if both are true ("T"), I put T in the fifth column, otherwise I put F.

A tautology is a formula which is "always truthful" --- that is, it is true for every assignment of truth values to its uncomplicated components. You can think of a tautology equally a rule of logic.

The reverse of a tautology is a contradiction, a formula which is "always imitation". In other words, a contradiction is false for every consignment of truth values to its simple components.

Example. Show that ![]() is a tautology.

is a tautology.

I construct the truth table for ![]() and show that the formula is always true.

and show that the formula is always true.

The last column contains only T's. Therefore, the formula is a tautology.![]()

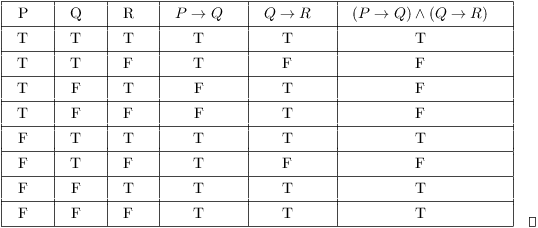

Example. Construct a truth table for ![]() .

.

Yous tin encounter that constructing truth tables for statements with lots of connectives or lots of unproblematic statements is pretty ho-hum and error-prone. While there might exist some applications of this (e.g. to digital circuits), at some point the best matter would be to write a program to construct truth tables (and this has surely been done).

The bespeak here is to empathise how the truth value of a circuitous statement depends on the truth values of its elementary statements and its logical connectives. In well-nigh work, mathematicians don't usually use statements which are very complicated from a logical bespeak of view.

Example. (a) Suppose that P is false and ![]() is true. Tell whether Q is true, false, or its truth value tin can't be determined.

is true. Tell whether Q is true, false, or its truth value tin can't be determined.

(b) Suppose that ![]() is fake. Tell whether Q is true, false, or its truth value tin can't be determined.

is fake. Tell whether Q is true, false, or its truth value tin can't be determined.

(a) Since ![]() is true, either P is true or

is true, either P is true or ![]() is true. Since P is false,

is true. Since P is false, ![]() must be true. Hence, Q must be false.

must be true. Hence, Q must be false.![]()

(b) An if-then statement is false when the "if" part is truthful and the "and so" part is false. Since ![]() is false,

is false, ![]() is truthful. An "and" statement is true only when both parts are true. In particular,

is truthful. An "and" statement is true only when both parts are true. In particular, ![]() must be truthful, so Q is fake.

must be truthful, so Q is fake.![]()

Example. Suppose

"![]() " is true.

" is true.

"![]() " is imitation.

" is imitation.

"Calvin Pudgy has majestic socks" is true.

Determine the truth value of the argument

![]()

For simplicity, let

P = "![]() ".

".

Q = "![]() ".

".

R = "Calvin Butterball has royal socks".

I desire to determine the truth value of ![]() . Since I was given specific truth values for P, Q, and R, I set upwardly a truth table with a single row using the given values for P, Q, and R:

. Since I was given specific truth values for P, Q, and R, I set upwardly a truth table with a single row using the given values for P, Q, and R:

Therefore, the statement is true.![]()

Instance. Determine the truth value of the statement

![]()

The statement "![]() " is faux. Y'all can't tell whether the statement "Ichabod Xerxes eats chocolate cupcakes" is true or false --- just information technology doesn't matter. If the "if" part of an "if-and so" statement is fake, then the "if-then" statement is true. (Check the truth tabular array for

" is faux. Y'all can't tell whether the statement "Ichabod Xerxes eats chocolate cupcakes" is true or false --- just information technology doesn't matter. If the "if" part of an "if-and so" statement is fake, then the "if-then" statement is true. (Check the truth tabular array for ![]() if you're not certain about this!) So the given argument must exist truthful.

if you're not certain about this!) So the given argument must exist truthful.![]()

Two statements X and Y are logically equivalent if ![]() is a tautology. Another way to say this is: For each assignment of truth values to the elementary statements which make up 10 and Y, the statements 10 and Y have identical truth values.

is a tautology. Another way to say this is: For each assignment of truth values to the elementary statements which make up 10 and Y, the statements 10 and Y have identical truth values.

From a applied point of view, y'all can supplant a statement in a proof by whatsoever logically equivalent statement.

To test whether X and Y are logically equivalent, you could gear up a truth table to test whether ![]() is a tautology --- that is, whether

is a tautology --- that is, whether ![]() "has all T's in its column". However, it'south easier to set a tabular array containing X and Y so check whether the columns for X and for Y are the aforementioned.

"has all T's in its column". However, it'south easier to set a tabular array containing X and Y so check whether the columns for X and for Y are the aforementioned.

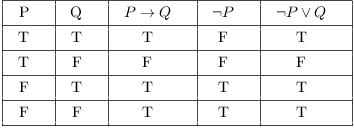

Example. Show that ![]() and

and ![]() are logically equivalent.

are logically equivalent.

Since the columns for ![]() and

and ![]() are identical, the two statements are logically equivalent. This tautology is called Provisional Disjunction. You lot tin can employ this equivalence to replace a conditional by a disjunction.

are identical, the two statements are logically equivalent. This tautology is called Provisional Disjunction. You lot tin can employ this equivalence to replace a conditional by a disjunction.![]()

There are an infinite number of tautologies and logical equivalences; I've listed a few below; a more extensive list is given at the end of this section.

![$$\matrix{ \hbox{Double negation} & \lnot(\lnot P) \iff P \cr \hbox{DeMorgan's Law} & \lnot(P \lor Q) \iff (\lnot P \land \lnot Q) \cr \hbox{DeMorgan's Law} & \lnot(P \land Q) \iff (\lnot P \lor \lnot Q) \cr \hbox{Contrapositive} & (P \ifthen Q) \iff (\lnot Q \ifthen\,\lnot P) \cr \hbox{Modus ponens} & [P \land (P \ifthen Q)] \ifthen Q \cr \hbox{Modus tollens} & [\lnot Q \land (P \ifthen Q)] \ifthen\,\lnot P \cr}$$](https://sites.millersville.edu/bikenaga/math-proof/truth-tables/truth-tables63.png)

When a tautology has the form of a biconditional, the two statements which make up the biconditional are logically equivalent. Hence, you can supercede one side with the other without changing the logical meaning.

Y'all will often demand to negate a mathematical argument. To see how to practise this, we'll brainstorm by showing how to negate symbolic statements.

Example. Write down the negation of the following statements, simplifying so that only unproblematic statements are negated.

(a) ![]()

(b) ![]()

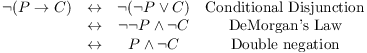

(a) I negate the given statement, then simplify using logical equivalences. I've given the names of the logical equivalences on the right so y'all can see which ones I used.

![]()

(b)

![$$\matrix{\lnot[(P \land Q) \ifthen R] & \iff & \lnot[\lnot(P \land Q) \lor R] & \hbox{Conditional Disjunction} \cr & \iff & \lnot\lnot(P \land Q) \land \lnot R & \hbox{DeMorgan's law} \cr & \iff & (P \land Q) \land \lnot R & \hbox{Double negation} \cr}$$](https://sites.millersville.edu/bikenaga/math-proof/truth-tables/truth-tables67.png)

I showed that ![]() and

and ![]() are logically equivalent in an before example.

are logically equivalent in an before example.![]()

In the post-obit examples, nosotros'll negate statements written in words. This is more than typical of what you'll need to do in mathematics. The idea is to catechumen the word-statement to a symbolic statement, so use logical equivalences as we did in the last example.

Example. Use DeMorgan's Constabulary to write the negation of the post-obit statement, simplifying so that only simple statements are negated:

"Calvin is not home or Bonzo is at the movies."

Allow C exist the statement "Calvin is abode" and let B exist the statement "Bonzo is at the moves". The given argument is ![]() . I'm supposed to negate the statement, then simplify:

. I'm supposed to negate the statement, then simplify:

![]()

The outcome is "Calvin is home and Bonzo is not at the movies".![]()

Example. Use DeMorgan's Law to write the negation of the following argument, simplifying so that only simple statements are negated:

"If Phoebe buys a pizza, so Calvin buys popcorn."

Permit P be the statement "Phoebe buys a pizza" and let C be the statement "Calvin buys popcorn". The given statement is ![]() . To simplify the negation, I'll use the Conditional Disjunction tautology which says

. To simplify the negation, I'll use the Conditional Disjunction tautology which says

![]()

That is, I tin can supplant ![]() with

with ![]() (or vice versa).

(or vice versa).

Here, then, is the negation and simplification:

The result is "Phoebe buys the pizza and Calvin doesn't buy popcorn".![]()

Next, we'll apply our work on truth tables and negating statements to bug involving constructing the antipodal, inverse, and contrapositive of an "if-then" statement.

Case. Replace the following argument with its contrapositive:

"If x and y are rational, then ![]() is rational."

is rational."

By the contrapositive equivalence, this argument is the same as "If ![]() is not rational, then it is not the case that both x and y are rational".

is not rational, then it is not the case that both x and y are rational".

This answer is correct as it stands, just we tin can limited it in a slightly ameliorate fashion which removes some of the explicit negations. Almost people find a positive statement easier to comprehend than a negative statement.

By definition, a real number is irrational if it is non rational. So I could replace the "if" part of the contrapositive with "![]() is irrational".

is irrational".

The "and then" part of the contrapositive is the negation of an "and" statement. You could recapitulate information technology every bit "It'south not the case that both x is rational and y is rational". (The give-and-take "both" ensures that the negation applies to the whole "and" statement, not merely to "x is rational".)

By DeMorgan'south Police, this is equivalent to: "x is not rational or y is not rational". Alternatively, I could say: "x is irrational or y is irrational".

Putting everything together, I could limited the contrapositive as: "If ![]() is irrational, and then either x is irrational or y is irrational".

is irrational, and then either x is irrational or y is irrational".

(Every bit usual, I added the word "either" to brand it clear that the "then" function is the whole "or" argument.)![]()

Example. Show that the inverse and the antipodal of a conditional are logically equivalent.

Let ![]() be the conditional. The changed is

be the conditional. The changed is ![]() . The converse is

. The converse is ![]() .

.

I could show that the inverse and antipodal are equivalent past amalgam a truth table for ![]() . I'll use some known tautologies instead.

. I'll use some known tautologies instead.

Commencement with ![]() :

:

![]()

Call up that I can replace a argument with one that is logically equivalent. For example, in the last step I replaced ![]() with Q, considering the two statements are equivalent by Double negation.

with Q, considering the two statements are equivalent by Double negation.![]()

Example. Suppose x is a real number. Consider the statement

"If ![]() , and then

, and then ![]() ."

."

Construct the converse, the inverse, and the contrapositive. Decide the truth or falsity of the 4 statements --- the original statement, the converse, the inverse, and the contrapositive --- using your knowledge of algebra.

The antipodal is "If ![]() , then

, then ![]() ".

".

The inverse is "If ![]() , and then

, and then ![]() ".

".

The contrapositive is "If ![]() , then

, then ![]() ".

".

The original statement is false: ![]() , but

, but ![]() . Since the original statement is eqiuivalent to the contrapositive, the contrapositive must be false also.

. Since the original statement is eqiuivalent to the contrapositive, the contrapositive must be false also.

The converse is true. The inverse is logically equivalent to the antipodal, so the inverse is truthful as well.![]()

\newpage

\centerline{\bigssbold List of Tautologies}

![$$\matrix{ 1. \hfill & P \lor \lnot P \hfill & \hbox{Law of the excluded middle} \hfill \cr 2. \hfill & \lnot(P \land \lnot P) \hfill & \hbox{Contradiction} \hfill \cr 3. \hfill & [(P \ifthen Q) \land \lnot Q] \ifthen \lnot P \hfill & \hbox{ Modus tollens} \hfill \cr 4. \hfill & \lnot\lnot P \iff P \hfill & \hbox{Double negation} \hfill \cr 5. \hfill & [(P \ifthen Q) \land (Q \ifthen R)] \ifthen (P \ifthen R) \hfill & \hbox{Law of the syllogism} \hfill \cr 6. \hfill & (P \land Q) \ifthen P \hfill & \hbox{Decomposing a conjunction} \hfill \cr & (P \land Q) \ifthen Q \hfill & \hbox{Decomposing a conjunction} \hfill \cr 7. \hfill & P \ifthen (P \lor Q) \hfill & \hbox{Constructing a disjunction} \hfill \cr & Q \ifthen (P \lor Q) \hfill & \hbox{Constructing a disjunction} \hfill \cr 8. \hfill & (P \iff Q) \iff [(P \ifthen Q) \land (Q \ifthen P)] \hfill & \hbox{Definition of the biconditional} \hfill \cr 9. \hfill & (P \land Q) \iff (Q \land P) \hfill & \hbox{Commutative law for $\land$} \hfill \cr 10. \hfill & (P \lor Q) \iff (Q \lor P) \hfill & \hbox{Commutative law for $\lor$} \hfill \cr 11. \hfill & [(P \land Q) \land R] \iff [P \land (Q \land R)] \hfill & \hbox{Associative law for $\land$} \hfill \cr 12. \hfill & [(P \lor Q) \lor R] \iff [P \lor (Q \lor R)] \hfill & \hbox{Associative law for $\lor$} \hfill \cr 13. \hfill & \lnot(P \lor Q) \iff (\lnot P \land \lnot Q) \hfill & \hbox{DeMorgan's law} \hfill \cr 14. \hfill & \lnot(P \land Q) \iff (\lnot P \lor \lnot Q) \hfill & \hbox{DeMorgan's law} \hfill \cr 15. \hfill & [P \land (Q \lor R)] \iff [(P \land Q) \lor (P \land R)] \hfill & \hbox{Distributivity} \hfill \cr 16. \hfill & [P \lor (Q \land R)] \iff [(P \lor Q) \land (P \lor R)] \hfill & \hbox{Distributivity} \hfill \cr 17. \hfill & (P \ifthen Q) \iff (\lnot Q \ifthen \lnot P) \hfill & \hbox{Contrapositive} \hfill \cr 18. \hfill & (P \ifthen Q) \iff (\lnot P \lor Q) \hfill & \hbox{Conditional disjunction} \hfill \cr 19. \hfill & [(P \lor Q) \land \lnot P] \ifthen Q \hfill & \hbox{Disjunctive syllogism} \hfill \cr 20. \hfill & (P \lor P) \iff P \hfill & \hbox{Simplification} \hfill \cr 21. \hfill & (P \land P) \iff P \hfill & \hbox{Simplification} \hfill \cr}$$](https://sites.millersville.edu/bikenaga/math-proof/truth-tables/truth-tables98.png)

Contact information

Bruce Ikenaga's Home Page

Copyright 2022 past Bruce Ikenaga

Source: https://sites.millersville.edu/bikenaga/math-proof/truth-tables/truth-tables.html

0 Response to "Which of the Following Statements Can Be Used to Prove That Carbon Is Tetrahedral?"

Post a Comment